Evidence-Based Strategies for a Knowledgeable Fitness Audience

Definitive Guide to Reducing Belly Fat:

All rights reserved. The author and publisher have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of information presented. However, they disclaim any liability for errors, omissions, or outcomes resulting from the application of this information. Always consult with a healthcare professional before beginning any new fitness or nutrition program.

Introduction

Table of Contents

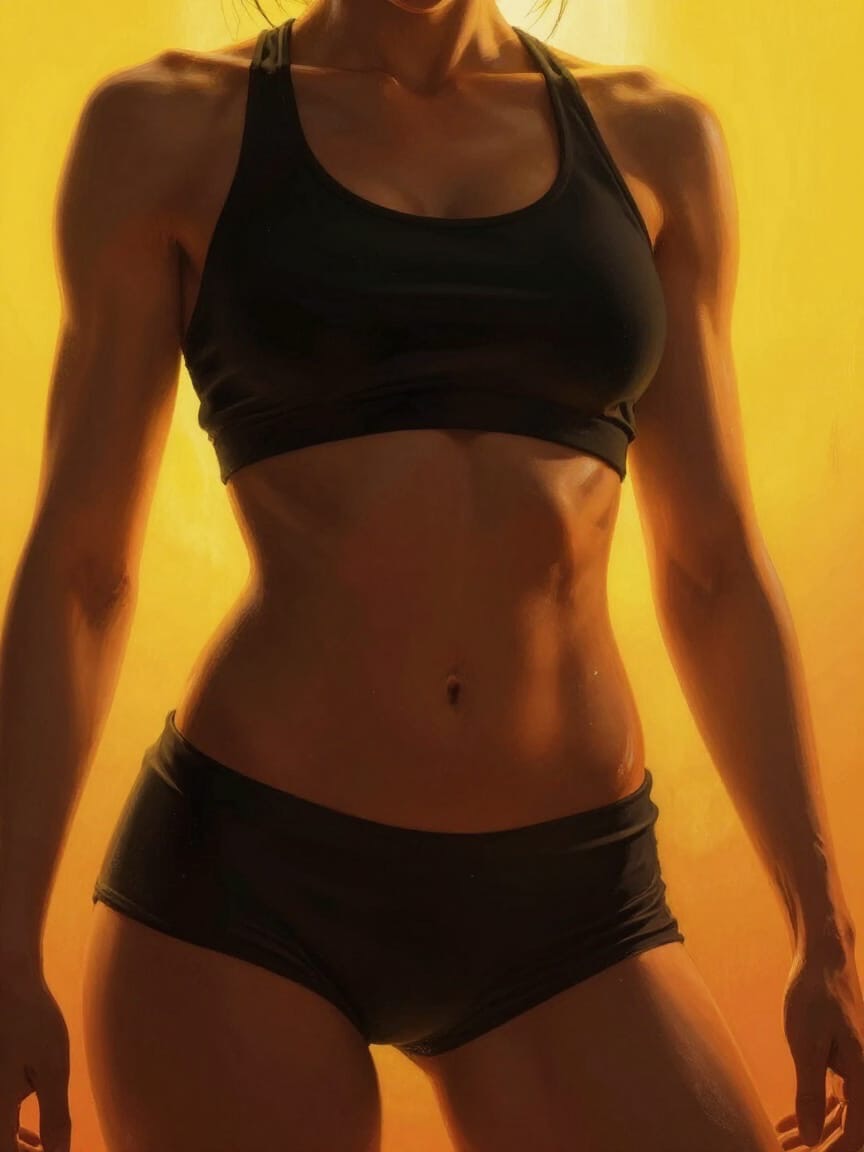

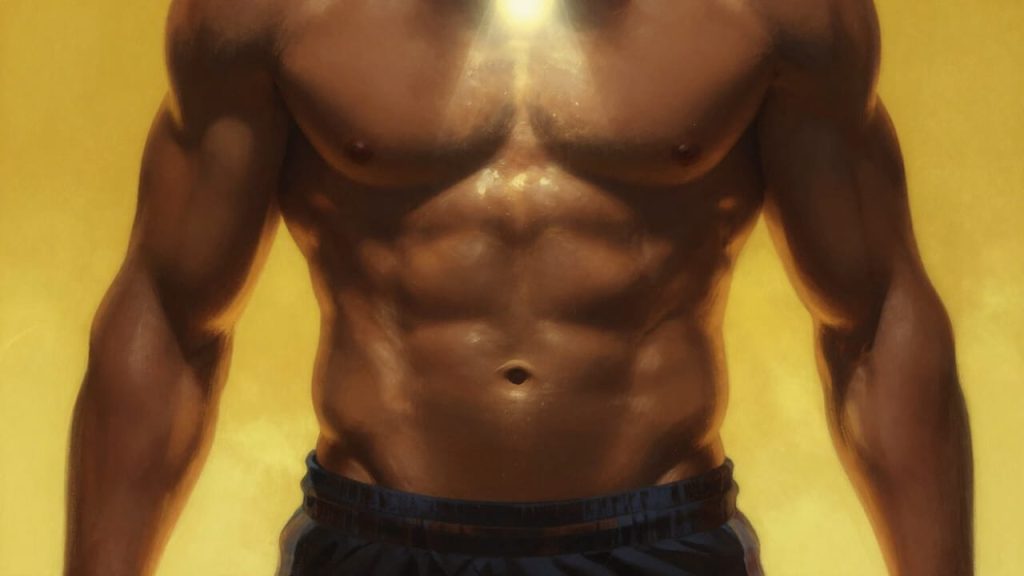

Belly Fat: Whether you’ve been pursuing fitness goals for years or are beginning your journey toward better health, you likely recognize that not all fat is created equal.

Visceral fat—the adipose tissue that accumulates deep within the abdominal cavity—represents a distinct metabolic challenge and health risk.

This guide provides a science-backed framework for understanding and reducing visceral fat. You’ll discover not just what to do, but why these strategies work, equipping you with knowledge to build a sustainable, effective approach.

What you’ll find here:

- A clear understanding of visceral fat biology

- Research-supported methods for targeted reduction

- Practical strategies for immediate implementation

- A foundation for lasting metabolic health

Let’s begin by assessing your current status, exploring the unique nature of visceral fat, and detailing the 10 evidence-based strategies used by fitness professionals.

Understanding Visceral Fat

Assessment: Do You Have Excess Visceral Fat?

The most practical method for assessing visceral fat accumulation is waist circumference measurement. Unlike BMI or scale weight alone, this measurement specifically indicates abdominal adiposity.

Measurement Protocol:

- Measure at your natural waistline, typically just above the navel

- Ensure the tape is horizontal and snug but not compressing skin

- Take measurements consistently (morning, before eating)

Health Thresholds:

- Women: < 35 inches (88 cm)

- Men: < 40 inches (102 cm)

Exceeding these measurements correlates with increased health risks regardless of overall weight. Individuals within “normal” BMI ranges but with elevated waist circumference still face heightened metabolic risks.

Important: The strategies outlined here effectively address both overall weight management and specific visceral fat reduction.

How Visceral Fat Differs from Subcutaneous Fat

While subcutaneous fat is primarily a cosmetic concern in excess, visceral fat is an active driver of chronic disease. The goal for health is not necessarily to have the lowest total fat mass, but to specifically minimize the metabolically toxic visceral fat depot through the targeted strategies outlined in the main

This understanding empowers you to focus on what truly matters for metabolic health, rather than just cosmetic appearance or scale weight alone.

Core Distinctions at a Glance

| Characteristic | Visceral Fat (Deep Belly Fat) | Subcutaneous Fat (Under-the-Skin Fat) |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Deep within abdominal cavity, surrounding organs (liver, intestines, pancreas) | Directly beneath the skin, distributed over entire body (thighs, hips, arms, abdomen) |

| Primary Function | Active endocrine organ; rapid energy source for “fight or flight” | Long-term energy storage; insulation and cushioning |

| Metabolic Activity | Highly active – secretes hormones & inflammatory chemicals | Relatively inert – primarily stores energy |

| Mobilization Rate | Gains and loses relatively quickly in response to hormones (cortisol, insulin) | Gains and loses slowly; more resistant to change |

| Health Risk | High – Directly linked to chronic disease | Low-to-Moderate – Can be protective in moderate amounts |

| Body Shape Association | Apple shape (central obesity) | Pear shape (hip/thigh focused) |

The Four Types of Adipose Tissue

- Brown Adipose Tissue (BAT)

- Metabolically active, generates heat through thermogenesis

- More prevalent in lean individuals and children

- Can be activated through cold exposure and certain exercises

- White Adipose Tissue

- Primary energy storage depot

- Endocrine organ secreting adipokines

- Subcutaneous and visceral are subtypes

- Subcutaneous Fat

- Located beneath the skin

- Measured via skinfold calipers

- Less metabolically active than visceral fat

- Visceral Fat

- Surrounds internal organs

- Highly metabolically active

- Strongly linked to insulin resistance and inflammation

Why Visceral Fat Matters

Research presented at the European Society of Cardiology (2012) demonstrated that individuals with concentrated visceral fat had a 50% higher all-cause mortality risk compared to those with generalized obesity. Unlike subcutaneous fat, visceral adipose tissue:

- Releases inflammatory cytokines

- Contributes to insulin resistance

- Disrupts normal hormone signaling

- Is linked to increased cardiovascular risk

Primary Contributors to Visceral Fat Accumulation

- Genetic Predisposition: Inheritance patterns affect fat distribution

- Hormonal Changes: Reduced estrogen (menopause) and elevated cortisol

- Chronic Stress: Sustained cortisol elevation promotes abdominal fat storage

- Dietary Factors: High glycemic load, excessive fructose, poor fatty acid balance

- Insulin Resistance: Creates a cycle of fat storage and metabolic dysfunction

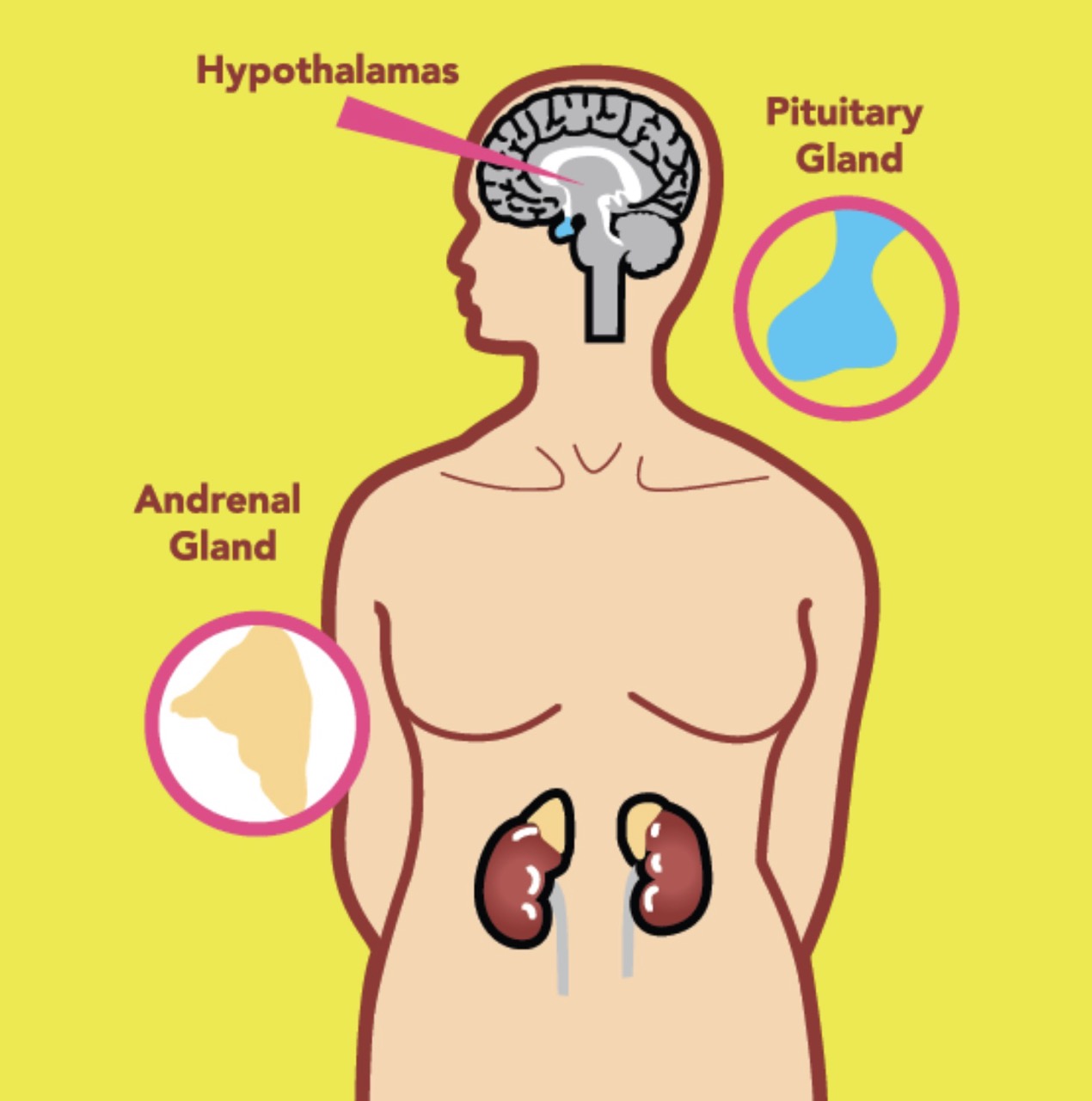

Elevated cortisol specifically contributes through multiple mechanisms, including increased appetite, preferential abdominal fat storage, and metabolic alterations.

Notes

The adrenal glands, hypothalamus, and pituitary gland form a command-and-control circuit called the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis. This is the body’s central stress response system, and it has a profound, direct connection to fat metabolism, storage location, and overall body composition.

Creators Notebook

When digital note taking isn’t an option reach for your traditional artists notebook wherever you go.

Whether crafting a masterpiece or brainstorming the next big idea, this notebook will inspire your inner wordsmith. The product features 80 lined, cream-colored pages, a built-in elastic closure, and a matching ribbon page marker. Plus, the expandable inner pocket—perfect for storing loose notes and business

10 Evidence-Based Strategies to Reduce Visceral Fat

Important Perspective: These strategies represent sustainable lifestyle adjustments, not quick fixes. Visceral fat accumulation occurs over time, and reduction follows the same pattern. Consistency, not perfection, drives results.

1. Stress Management

Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which directly promotes visceral fat storage. Effective management reduces this hormonal driver.

Evidence-Based Techniques:

- Diaphragmatic Breathing: Slow, controlled breaths (4-7-8 pattern) to activate parasympathetic response

- Mindfulness Meditation: 10-20 minutes daily to reduce perceived stress

- Scheduled Worry Time: Contain anxiety to specific, limited periods

- Professional Support: Cognitive-behavioral approaches for persistent stress

2. Hydration Optimization

Dehydration stimulates cortisol release. Adequate hydration supports metabolic processes and stress resilience.

Implementation:

- Daily Minimum: 0.5-1 ounce per pound of body weight (adjust for activity, climate)

- Strategic Timing: 16-20 oz upon waking; consistent intake throughout day

- Quality Matters: Filtered water; limit diuretics (caffeine, alcohol)

- Enhancement: Add electrolytes during intense training or heat exposure

3. Strategic Exercise Programming

Traditional steady-state cardio may exacerbate cortisol response. A balanced approach yields better results.

Optimal Protocol:

- Resistance Training: 3-4 sessions weekly, 40-60 minutes, compound movements

- High-Intensity Interval Training: 2-3 sessions weekly, 20-30 minutes

- Low-Intensity Activity: 8,000-12,000 daily steps (non-exercise activity thermogenesis)

- Mind-Body Practices: Yoga, Tai Chi (shown to modulate cortisol response)

Note: Avoid training the same muscle groups consecutively; allow 48-hour recovery.

4. Sleep Quality and Quantity

Sleep deprivation increases cortisol by approximately 45% and disrupts appetite-regulating hormones.

Sleep Hygiene Protocol:

- Duration: 7-9 hours nightly

- Consistency: Fixed sleep-wake times (±30 minutes)

- Environment: Complete darkness, 65-68°F, minimal noise

- Preparation: No screens 60 minutes before bed; consider magnesium supplementation

- Timing: Last meal 2-3 hours before sleep; protein-rich snack if needed closer to bedtime

5. Micronutrient Optimization: Vitamin C

Beyond its antioxidant role, vitamin C buffers stress response and supports cortisol metabolism.

Recommendations:

- Dietary Sources: Bell peppers, citrus, kiwi, broccoli, strawberries

- Supplementation: 500-1000 mg daily (consult healthcare provider)

- Synergy: Combine with magnesium and B vitamins for enhanced stress adaptation

6. Glycemic Control

High glycemic load foods spike insulin and cortisol, promoting visceral fat storage.

Implementation:

- Glycemic Awareness: Focus on low-moderate glycemic foods (non-starchy vegetables, legumes, most fruits)

- Fiber First: 30+ grams daily from diverse sources

- Meal Sequencing: Consume vegetables and protein before carbohydrates

- Timing: Larger carbohydrate meals around physical activity

7. Moderation of Alcohol and Caffeine

Both substances can dysregulate cortisol rhythms when consumed excessively or at suboptimal times.

Evidence-Based Guidelines:

- Alcohol: ≤1 drink daily for women, ≤2 for men; avoid daily consumption

- Caffeine: ≤400 mg daily; none within 8-10 hours of bedtime

- Individualization: Assess personal tolerance and timing effects

8. Dietary Fat Quality

Fat type influences where fat is stored. Monounsaturated and specific polyunsaturated fats may reduce visceral accumulation.

Optimal Fat Profile:

- Emphasize: Avocados, olive oil, nuts, seeds, fatty fish

- Moderate: Saturated fats (animal products, coconut)

- Minimize: Trans fats, processed seed oils

- Balance: Omega-6:Omega-3 ratio of 2:1 to 4:1

9. Social Connection

Loneliness and social isolation correlate with elevated cortisol and increased abdominal fat.

Building Connection:

- Regular Social Engagement: Weekly face-to-face interaction

- Shared Activities: Group training, sports, hobby groups

- Community Involvement: Volunteer work, community service

- Professional Support: Therapy for persistent loneliness or depression

10. Evidence-Supported Botanical Adjuncts

Certain herbs demonstrate cortisol-modulating properties through rigorous research.

Considerations:

- Ashwagandha: Shown to reduce cortisol and perceived stress

- Rhodiola Rosea: Adaptogen with fatigue-reducing effects

- Pharmaceutical-Grade Fish Oil: Anti-inflammatory, may support fat oxidation

- Important: Consult healthcare provider for interactions and appropriate dosing

Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes. Individual needs vary. Consult with qualified healthcare providers before implementing significant lifestyle changes, particularly if you have pre-existing health conditions.

Consistency, patience, and evidence-based practice yield sustainable results. Begin with one or two strategies, master them, then systematically incorporate additional elements. Your commitment to understanding and applying these principles will drive meaningful, lasting change.

You may find the following useful…

Persona Intelligent

MuseFYI

User Behavior Decoded

Bookkeeping vs Accounting

Disclosure: For your information, please note that products and services mentioned in our content may include links to businesses we have partnered with or have other association with (like those above). So when you sign up or make a purchase with our link, you also help support Software Folder with our continuing efforts to provide helpful content for free.

FAQ: Visceral (Belly) Fat Reduction

Q1: What exactly is visceral fat, and why is it more dangerous than subcutaneous fat?

A: Visceral fat is adipose tissue stored deep within the abdominal cavity, surrounding organs like the liver, pancreas, and intestines. Unlike subcutaneous fat (found just under the skin), visceral fat is metabolically active, secreting inflammatory cytokines and hormones that directly contribute to insulin resistance, systemic inflammation, and increased risk for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. Its location and biological activity make it a significant independent health risk factor, even in individuals with a normal BMI.

Q2: Can I “spot reduce” belly fat through specific exercises like crunches?

A: No. Spot reduction is a myth. While exercises like crunches can strengthen the underlying abdominal muscles (the rectus abdominis and obliques), they do not selectively burn the fat covering them. Fat loss occurs systemically in response to a sustained calorie deficit and favorable hormonal environment. The strategies that most effectively reduce visceral fat involve full-body metabolic stress (like resistance training and HIIT), nutrition, and lifestyle modifications that lower systemic insulin and cortisol levels.

Q3: Why is cortisol so central to visceral fat accumulation?

A: Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, plays a direct role in fat distribution. Chronically elevated cortisol levels:

Contribute to insulin resistance, creating a cycle that further promotes fat storage. Managing stress is therefore not just “for mental health” but a critical metabolic intervention.

Increase appetite, particularly for high-calorie, palatable foods.

Promote the storage of fat in the visceral adipose tissue, which has a high concentration of cortisol receptors.

Can break down muscle tissue for energy, lowering your metabolic rate over time.

Q4: Is long-duration steady-state cardio ineffective for losing belly fat?

A: It’s not inherently ineffective for creating a calorie deficit, but it may be suboptimal specifically for targeting visceral fat when used exclusively. Prolonged cardio sessions (e.g., >45-60 minutes) can elevate cortisol, potentially hindering visceral fat loss and compromising recovery. A more effective approach combines:

NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis): Consistent daily movement.

Resistance Training: Builds metabolically active muscle, improving insulin sensitivity.

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT): Creates significant metabolic disturbance and EPOC (Excess Post-Exercise Oxygen Consumption) with a lower time commitment and less cortisol impact than long cardio.